The LGBTQ retirees who don't want to become invisible, again

Written by Mikaela Wilkes for Stuff on November 15th 2021

Margaret Curnow, left and her partner Lou Brandon, in Brandon's Brooklyn home. The retired lesbian couple are in their 70s,and both live in central Wellington in their old family homes.

Margaret Curnow, 71, and her partner Lou Brandon plan to stay in their own Wellington homes for as long as they are able.

There are lots of reasons: Brandon's home is filled with her art collection, and a fabulous kitchen. Curnow’s biggest motivator is connection to community.

Brandon has a large collection of paintings.

But mostly, the lesbian couple say they don't want to be forced back into the closet in the last years of their lives.

Curnow has friends who have moved into retirement facilities and remain out, especially in Auckland. But she also has friends who hide their sexuality, and that's something she fears.

“Going into a village...you might not have any of your own tribe around you. We also don't want to have to deal with coming out again and again, to nasty reactions from our age group.

This central art work was painted by Brandon

“We've been there, done that,” she said. “We don’t want our relationship to be invisible.”

Recent research led by Mark Hendrickson of Massey University found that, while the attitudes of staff, residents and family members towards LGBTQ+ people in aged care are shifting, some elderly gay and trans people still hide their identities for fear of discrimination.

It's in line with the discrimination they’ve experienced for most of their lives.

“We weren't illegal like the men,” Curnow said. “But we were hassled on the street, yelled at for holding hands, and we didn’t have legal protections until the early 90s. We risked losing our jobs.

“I was working at a polytechnic had a complaint made against me for being a ‘self-declared practising lesbian’. I was lucky my boss’ wife was the minister for women’s affairs.”

Brandon with an old poster from a feminist event in England.

The baby boomer generation, who are now ageing into villages and care facilities, became adults before civil unions (2004) and marriage equality (2013) passed into law, Hendrickson said. Those aged 65 in 2019 were 33 years old in 1986, when homosexuality was decriminalised in New Zealand.

It’s a generation which fought for the rights of LGBTQ+ people, but that history can mean that homophobic and transphobic attitudes are more entrenched among some.

“We are seeing a great deal more acceptance in the millennial generation who came of age during and after these social policy changes,” he said. “Residents were aware that they mostly held the views of their generation; nonetheless they also looked to staff to set the tone.”

Some residents in aged care did experience acceptance, his study found. But other experiences ranged from ‘don’t ask, don't tell', to open hostility.

One resident said same-sex relationships would not be supported at his facility by staff: “They’d get really upset about that.” Another said openly gay people would be ostracised by other residents, who are “very, very conservative”. Some families had relatives they knew were gay, but weren't sure if this was relayed to staff.

One gay male facility manager mentioned a patient with cancer with a same-sex partner of more than 30 years, who he referred to as his friend in front of staff. “He'd say, ‘oh by the way, my friend is coming to visit me,’ and it saddened me. He had that self-protection, you know, guarding,” the manager said.

It's important to note that Hendrickson's study looked specifically at aged care facilities – not at retirement villages, or other housing models catering for older generations.

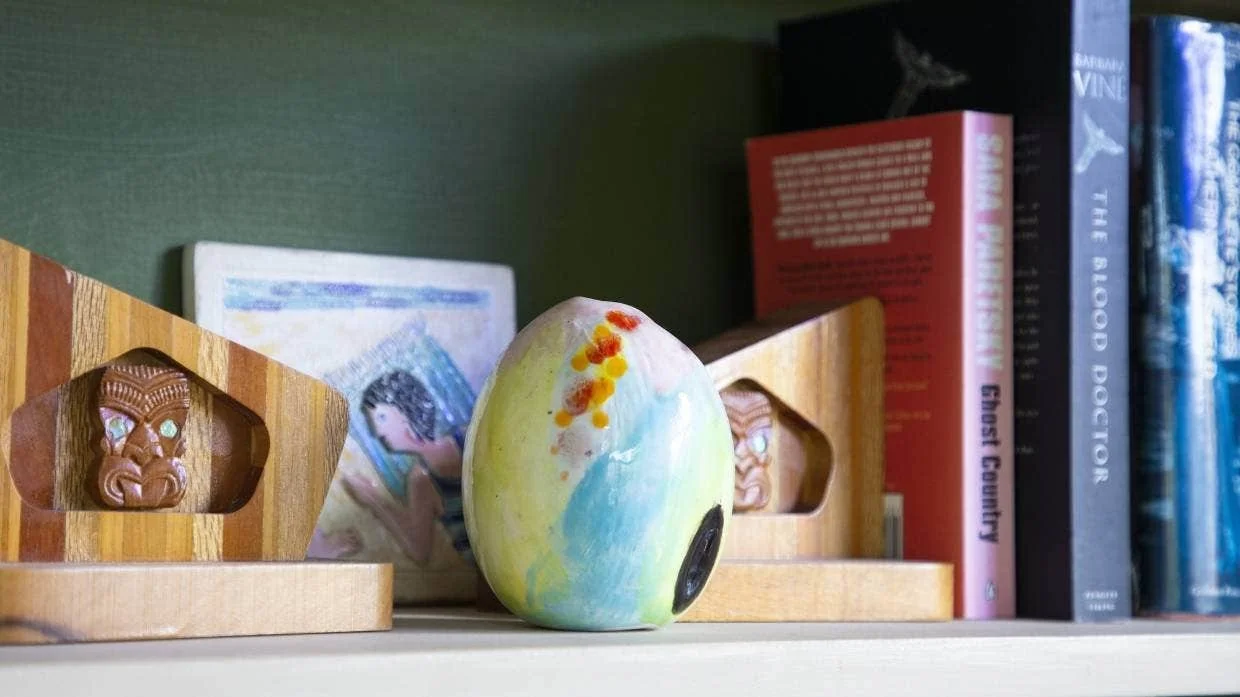

Brandon lives surrounded by art, including this ceramic piece by Jane Zusters.

However, in a separate study in 2010, Hendrickson found that LGBTQ+ people were least likely to choose living in a retirement community or facility, but if they were unable to live independently, they preferred that the facility catered for non-cis (a person whose gender identity is not the same as their sex assigned at birth) and non-heterosexual identities.

John Collyns, executive director of the Retirement Villages Association (RVA), said villages are generally more LGBTQ+ friendly and inclusive today than in the past.

A pot by Mirek Smisek on Brandon’s shelves.

“The average age of people moving into retirement villages is in the mid to late 70s,” he said. “LGBTQ+ people in this age group have faced very real consequences of discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity throughout their lives.”

The attitudes of existing residents plays a role in the culture of a village, Collyns said, but he wasn’t aware of any complaints or disputes relating to this.

“Some residents may never have knowingly met someone from the rainbow community before, so may not know how to react. Others will have much loved friends and family members who are LGBTQ+ and will be strong allies.

“What gives prospective residents the most confidence is seeing other rainbow community people already living in a village, but we stress that the absence of any LGBTQ+ residents doesn’t mean that they aren’t welcome.

“One of the most frequent comments our villages get from prospective residents is that they are impressed by the overall welcoming atmosphere, inclusivity, diversity and happiness.

“The best way for any prospective resident to determine whether a village will be a good fit is to visit and talk to staff and residents. We also recommend that anyone who has concerns about being accepted in a retirement village visits a few villages and see what they are all about.”

Simon Wallace, chief executive of the New Zealand Aged Care Association (NZACA), agreed. “While the report is right in saying there is a generational divide towards different sexual orientation, things are changing in aged residential care and the environment is more broadly reflective of what is happening in everyday society,” he said.

Curnow is open to the idea of moving to retirement village when she can no longer be independent. But after 40-something years of being out, she still worries about whether that environment will be an accepting one.

Lou Brandon, left, and her partner Marg Curnow in Lou’s Brooklyn, Wellington home. They would like to downsize into something more manageable, but haven’t been able to find something that fits the bill.

Connecting to the next generation

Ruth Busch is a friend of Curnow’s, and lives openly in an Anglican faith-based retirement village in Auckland with her partner.

“When we first moved in, the next-door-neighbour kind of peered at me and said ‘what is the nature of your relationship?’ I wasn’t interested in discussing that with her.”

Busch is a retired lawyer who represented gay and lesbian couples who wanted to retain custody of their children from prior marriages. She came out in 1979, “a really homophobic time”.

“Not one of us would have believed we'd ever see same-sex marriage. We were just despised.”

Busch has three children and nine grandchildren, something she said lesbian women of her era can use to mask their identity, as a safeguard against discrimination. Curnow also has three daughters. “But lots and lots in our generation didn’t have children, so they don’t have ready-made carers in old age,” said Curnow.

“They don't have someone to call on to help them with the lawns, or lift something heavy. We help each other out, but it's 70-year-olds helping other 70-year-olds,” she said, “and I’m less strong and able than I used to be.”

It would be nice if elderly gay people had a way of connecting with their millennial and Gen Z counterparts, Curnow said, because it’s a joy for them to see the next generations enjoying the rights they fought for, and continuing the kaupapa.

Training from the nurse to the manicurist

Hendrickson would like to see more education for staff in retirement villages and aged care in matters of sexuality and intimacy. It could cover a range of topics, such as the influence of ageing on erectile dysfunction and what pharmacy is available, how to set boundaries in a community-living setting, or how to date when you’re 80, he said. “It’s uncomfortable for family members, but there are a lot of sexual and romantic relationships in these places.”

Of the aged care staff he surveyed in 2020, 56.6 per cent agreed that same-sex couples have the right to be sexually intimate with one another, although younger staff were more likely to be supportive.

Some staff were not clear on the policies of their facility, and there were sometimes conflicts between what staff thought was best for residents, and what family members wanted, Hendrickson said.

He cited an occasion where the family of a trans resident with dementia insisted on using the person's pre-transition name and erasing their post-transition identity. The staff didn’t feel there was anything they could do, because the facility prioritised the wishes of the family member.

“There is very little resource available around caring for older trans persons, especially for those living with dementia who may forget that they’ve transitioned. That becomes incredibly complex,” Hendrickson said.

“I think the Ending Conversion Therapy legislation will protect older persons living with dementia in care, but those issues require really specialised training.

“We desperately need more education. And it has to start from the interview, all the way through on-boarding, and at least annually for all resident-facing staff. That means the gardener, the chef, the manicurist...”

Rest home providers who are part of the NZACA offer bi-annual staff training on sexuality and intimacy – it’s something which is contractually obliged, said Wallace.

“It is true that some residents may struggle to accept someone who they might perceive as different, but staff are well-trained in dealing with sexuality and intimacy are helping to change these perceptions.”

New Zealand Aged Care Association chief executive Simon Wallace said the rights of residents to personal relationships are protected.

Wallace said that NZACA members have a code of residents' rights, which protects the right to friendships and relationships, including intimate relationships, "provided the personal rights of others are protected".

He also noted that the aged care sector has “arguably one of the most diverse workforces in New Zealand”.

"As an association, we certainly encourage all our employers and their staff to support any and all residents regardless of their gender, sexual orientation or race.”

Julie Watson has been running the Silver Rainbow programme since 2016, a three-hour workshop teaching aged care workers how to be warm and welcoming to rainbow residents.

“It is really, really hard to change resident culture,” Watson said. “But what you can do is ensure that no staff member will turn a blind eye to homophobic or transphobic behaviour. They must role model what is acceptable.

“Many elderly people from LGBTTQIA+ communities had to hide who they were for a long time. Surely, in the last years of their lives they should be able to live without fear as their authentic selves.”

Tips for finding a rainbow-friendly retirement facility

Look for participation in programmes like Silver Rainbow, or ask what in-house training and education staff get.

Ask what the LGBTQ+ policies are. Does it have anti-discrimination policies? Does it have any experience in caring for LGBTQ+ seniors? Does it have any LGBTQ+ clubs or groups?

Visit several places in person to get a feel for what they are all about, and chat to the residents.

Ask whether you can have a trial. Some providers encourage these for prospective residents, or offer a money-back guarantee if it's not right for you within the first few months.

Think ahead and consider what you might need in the future. Will the facility be able to meet your other needs if your health or mobility declines?

Find out the total costs, and make sure you understand the financial and legal side of your contract.